Four Things I Learned from my Early Pregnancy Miscarriage

February 7th, 2026

Yesterday, I turned thirty years old. Twelve days before that, my first baby died in my womb and I began to miscarry. I was eight weeks and two days pregnant.

I had woken up, let the dogs out, and went to the bathroom to find blood. I woke up my husband and we rushed to the nearest ER, but there was nothing for them to do but run a couple of tests, give us the bad news, and send us home. Thus began the Lost Week. In the physical sense, it felt like the worst period of my life - though a few days into the week, my digestive system began to go haywire and the intestinal pain and discomfort only made the situation more difficult to bear on top of the severe cramping and fatigue. Hour after hour, I sat on the couch with my heating pad on full blast, my husband a few feet away, trying to simply stay alive through the darkness.

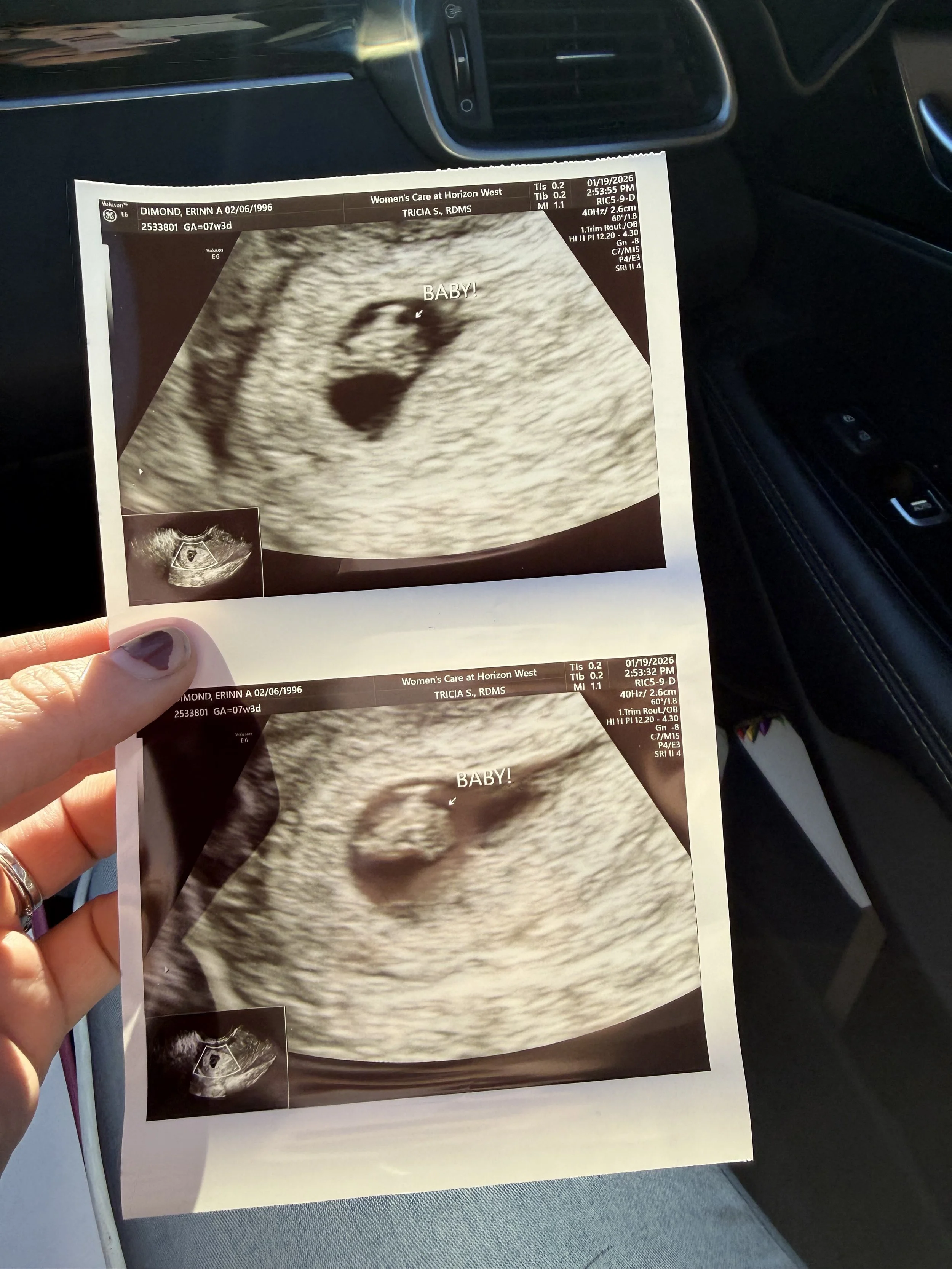

Within a month we went from wishing for a Christmas miracle, to witnessing that miracle’s heart beating on the ultrasound screen, to mourning the death of someone we barely knew but loved so, so much. And now, all I have left is a box - a wooden keepsake box containing the ultrasound picture, the pregnancy test, my ER bracelet and paperwork, and a onesie we had bought especially for this baby - and a faux-sapphire ring I bought off of eBay (sapphire would have been the baby’s birthstone if we had made it to term) that sits on my right hand.

I’ve been telling people that I’m okay, but really, I’m the farthest from okay that I’ve ever been. Answering the question of “How are you doing?” is just such a complicated endeavor that “You know, doing okay… it varies….” is just easier.

I’m so far from coming to terms with this loss, but here are four things I’ve learned from surviving my first miscarriage… so far.

The ones who don’t say anything stand out the loudest.

As we began to share the news of the death of our baby, we received many wonderful and kind texts and comments from loved ones and work friends. A few sent flowers, cards, a chocolate-covered fruit basket. Some have continued to check in on us, and though we never have a good update for them their continued care is appreciated.

But there are a few loved ones who haven’t said anything at all. People that have been in my life for years, even decades, who have professed to care deeply about me and my husband. But when we shared that we were in the darkest and most painful time of our lives, they were silent.

If you know someone who is grieving a traumatic loss, I urge you: say something. Don’t hide behind the excuse of “I don’t know what to say,” or “I don’t want to make things worse.” You simply can’t make things any worse than they already are. And frankly, you do know what to say. You can think of the bare minimum at the very least - after all, you’ve been saying “I’m sorry” your whole life. Add a “for your loss” to finish the sentence and sprinkle in a few niceties like “I’m praying for you,” “You can always talk to me,” and “We’ll always remember [name of the lost one]” and you’ve got yourself a passable condolence message.

Just, for goodness’ sake, don’t stay silent.

2. Say anything…. except “Let me know if there’s anything I can do.”

Many of the friends and relatives who offered their condolences said something along the lines of “Let me know if there’s anything I can do for you.” And as well-meaning as this sentence is, it’s actually really unhelpful.

The griever is not going to let you know what you can do. Most of the time it’s simply too exhausting to have to think of something specific, and asking for some sort of material assistance feels greedy.

“Can I do something for you? Do you need anything?”

Well, yeah, actually, Friend of Husband From Work. A crisp $100 bill and a DoorDash gift card would really come in handy, because the last thing I want to do while I labor to pass my lentil-sized baby is cook.

But I’m never going to tell someone that. I’m never going to tell them that what they can do for me is give me their hard-earned money so I can use it to spare myself some small amount of effort, or to cook for me or clean my house because I can barely move.

It feels greedy.

So the next time someone you love loses someone they love, don’t make a vague and generic offer of some undefined “help.” Make a decision about what you can actually, realistically, specifically do… and then offer that.

“I’ll be at the grocery store in an hour. Let me know what sounds good for dinner and I’ll drop it off.”

“Send me your grocery list and I’ll put in a DoorDash order for you.”

“I baked brownies - I’ll drop them off this afternoon. No need to open the door - just know I’m thinking of you.”

“I can babysit on Friday evening from 6pm to 9pm if you’d like to get out of the house.”

“I’ve got a mop, a bucket of cleaning supplies, and an energy drink - which room of your house needs the most TLC?”

“Check your email - I’ve sent over an Olive Garden gift card. They deliver now!”

Don’t just offer vague “help” - offer real action.

3. Prenatal care is not good enough in this country.

When I went in for my first ultrasound at seven weeks pregnant, the tech found that the baby was measuring a week small. A couple of blood tests revealed that my progesterone was dangerously low. I was given a progesterone supplement prescription, but by the time I started taking the pills it was too late.

It’s fair to assume that my progesterone was low the whole time I was pregnant, and that the lack of this vital hormone could be what caused my baby to die. After the OB confirmed that I had miscarried, she told me to let her know as soon as I find out I’m pregnant again. “We’ll get you in ASAP, we’ll test your hormones, and we’ll get you on supplements if any are low,” she said. “We’ll give the next baby the best chance we can.”

So why was my first blood test for this baby done at seven weeks and a few days pregnant? Why is the medical standard not a blood test as early as possible? Why did someone have to die before early intervention was offered to me? I understand that the medical system is overrun and short-staffed, but it takes a half hour or less to run a blood test. I just can’t believe that it would burden the system that much to simply have pregnant women come in for a standard blood test as soon as they find out they’re pregnant. Then, necessary preventative interventions can be given as early as possible.

Had I been given extra progesterone at four weeks pregnant - when I first found out - instead of seven, would it have saved my baby? Maybe not. But maybe so. And if there’s a chance, then it’s worth trying.

4. There are some traumas that are just too big.

There are so many aspects to losing a child during pregnancy that are just dark. Horrific. But for me, two specific components have stood out and cut deeper than the rest.

The first is that my womb, which is created to be a garden in which God creates and nourishes and grows life, has become a grave. There was a second life in my body and then there was death inside me. Death where there should never be.

The second is that I was unable to bury my own baby because his or her little body was too small for me to find amidst the blood clots and wasted amniotic fluid leaving the grave site. I couldn’t find my baby’s body so I was forced to flush my own child down the toilet. Instead of a Mass for the Dead and a mahogony box, my firstborn was given the same treatment as a goldfish.

These twin traumas have merged to become a dark hole in my heart that I know I’ll never be able to explore. I know that if I enter that hole, I’ll never find my way back out.

So, all I can do is put a lid over the hole, stap it down, add a few padlocks, and try to live with it.